Memory House

A series of sketches and notes on the spaces I’ve called home, and the sensory traces they leave behind.

We don’t remember spaces the way architects draw them.

We remember them as moods. As sensations. As fleeting impressions stored somewhere between body and mind.

The cold tile under bare feet on a winter morning.

The smoothness of a handrail worn down by years of touch.

The way dusk filtered through a window and softened the edges of a room.

One of the books that has shaped how I think about this is The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard. Bachelard argues that it isn’t the grand architecture of a place we carry with us, but its intimate details—the corners, textures, thresholds, and sensations that shape our daydreams. We imagine the home from within, not as an object, but as an experience.

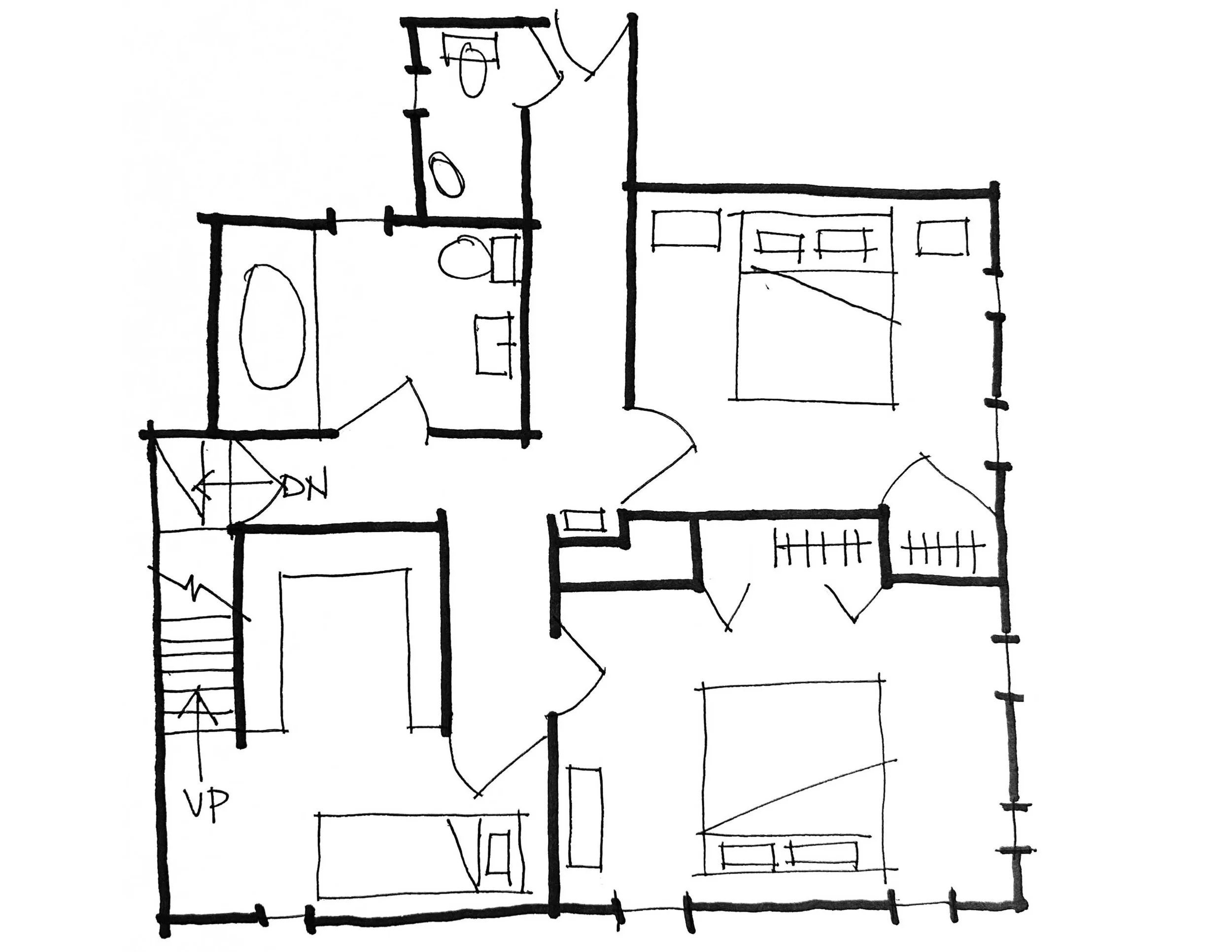

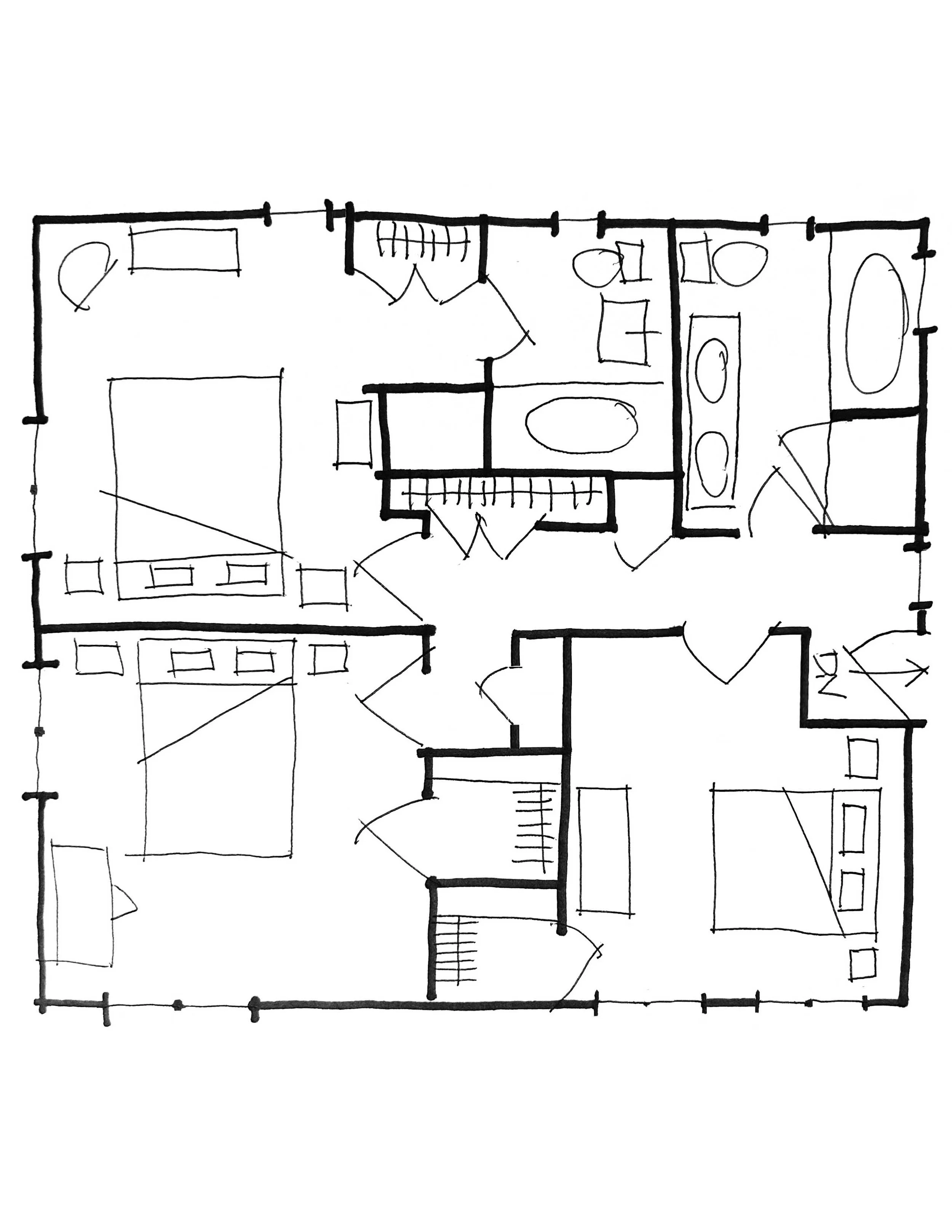

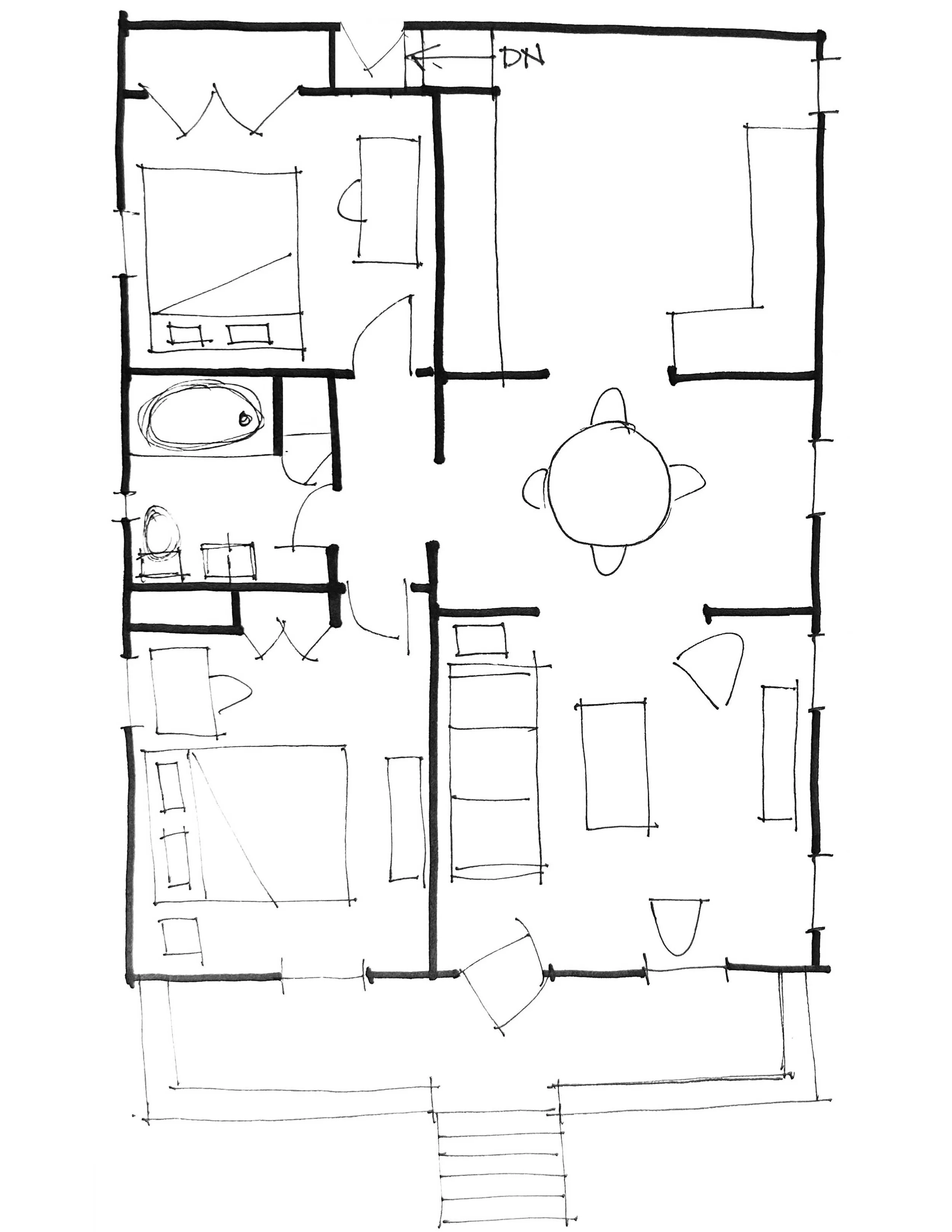

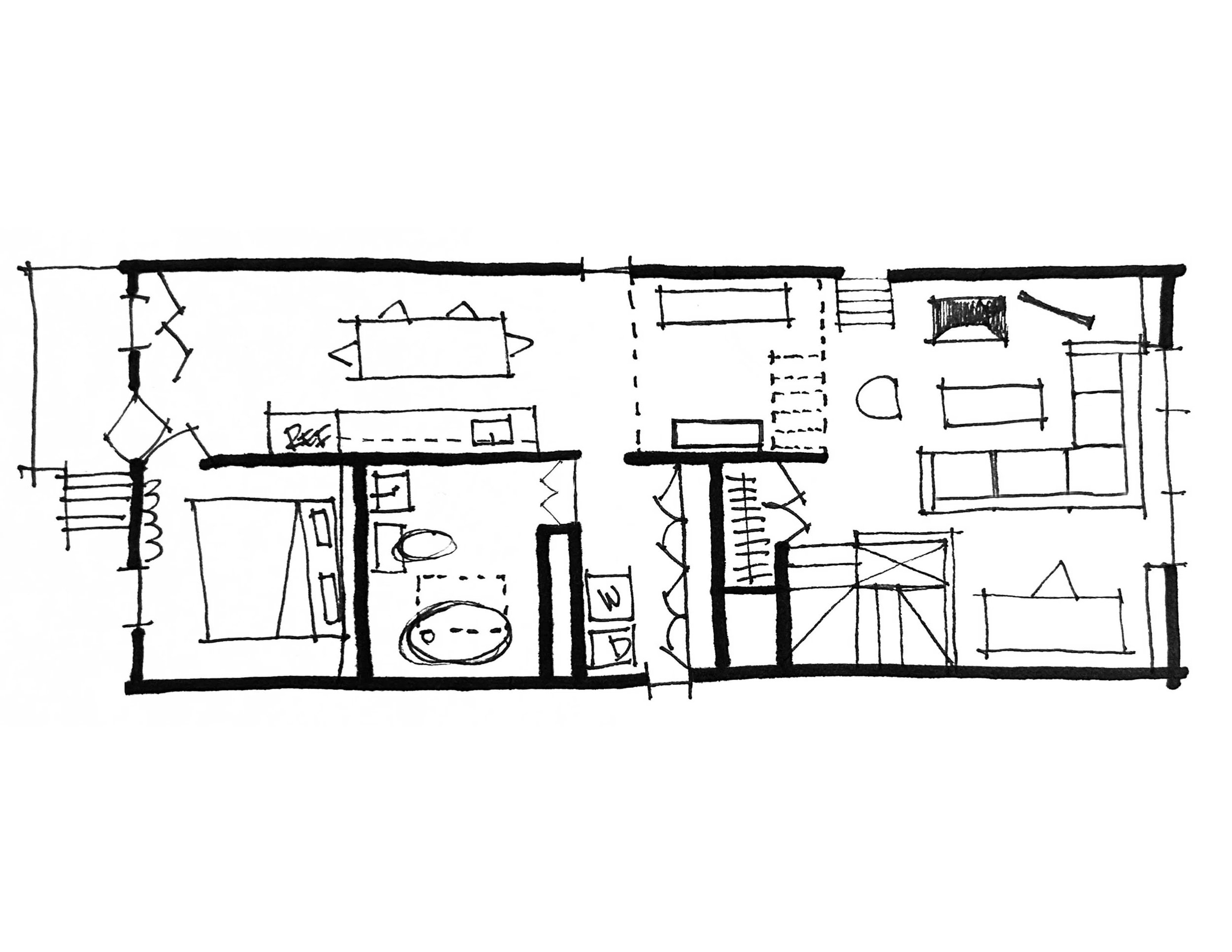

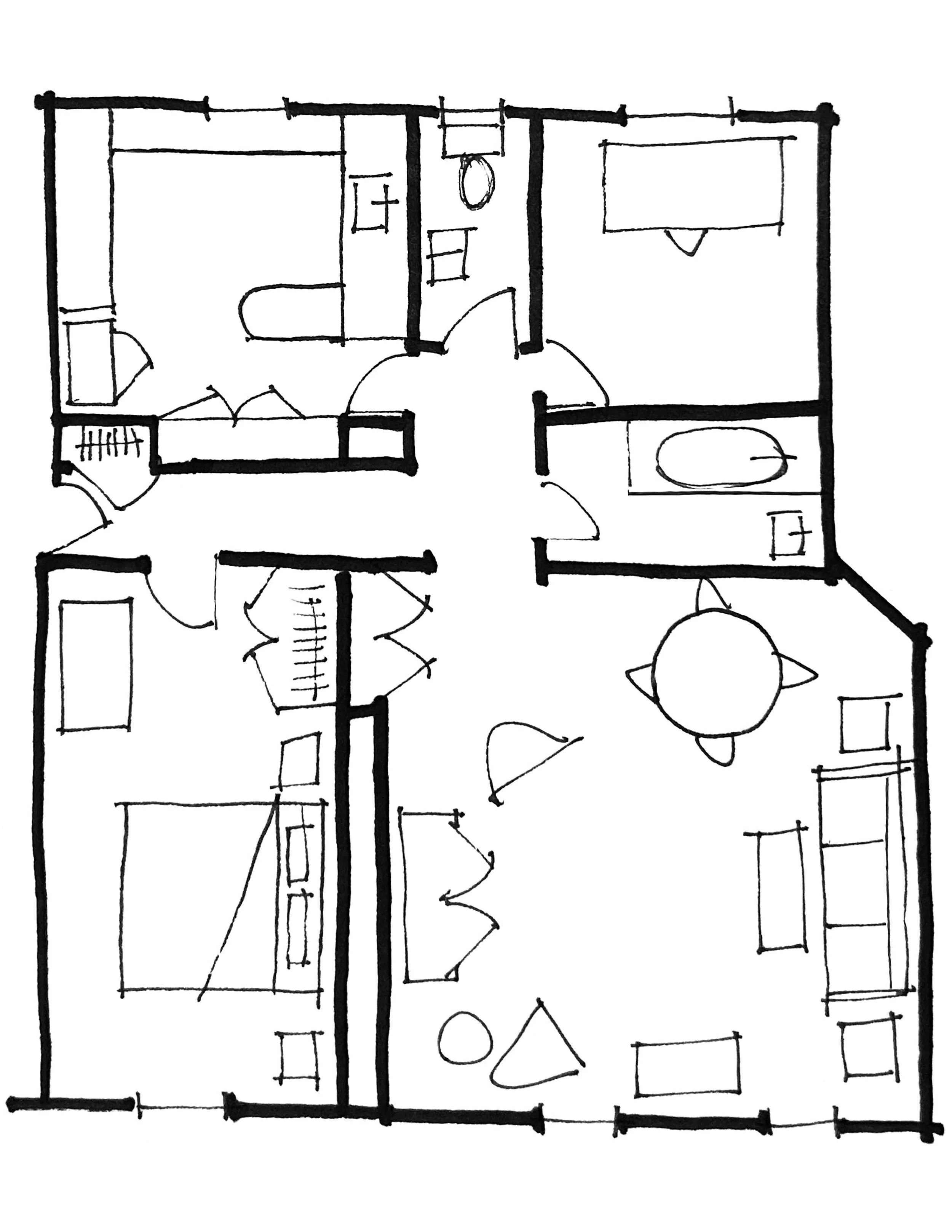

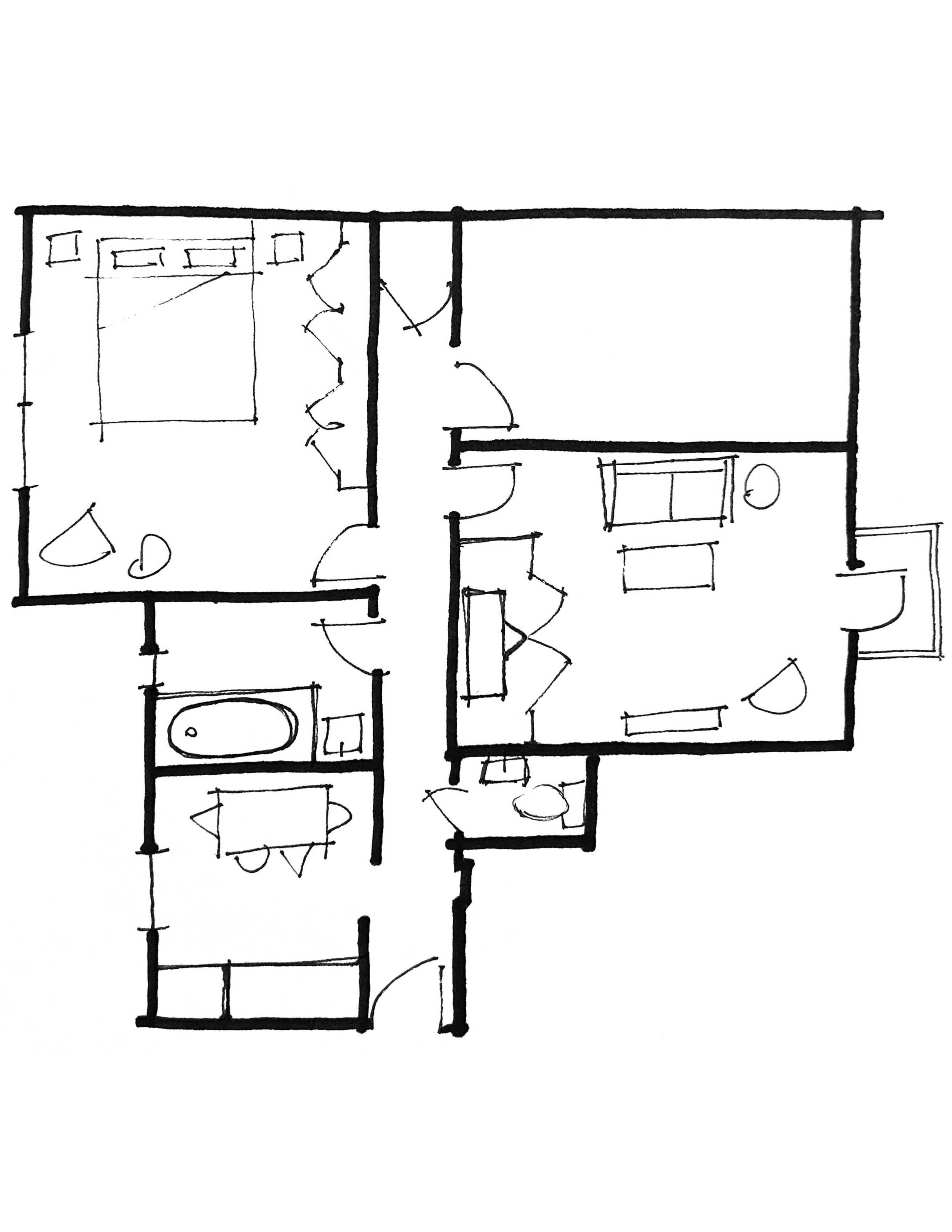

In this journal entry, I’ve sketched from memory the places I’ve lived. Not to capture their plans or finishes with accuracy, but to trace the feeling of them. These are the memories I return to when I’m getting to know a client, when I’m trying to understand the soul of a home. What stays with us, often, are the things we didn’t consciously notice at the time—the atmosphere of life.

Bachelard writes about how even the smallest spaces can feel vast inside our imagination: the attic, a window bench, a childhood hideout. Memory magnifies and distills space beyond its real dimensions. Pillow forts. Hiding behind a couch. The choreography of moving from entryway to corridor to living room. These remembered spaces detach themselves from reality and become something else entirely.

When I draw plans from memory, I notice the quirks. I sometimes catch myself “fixing” them—improving proportions, correcting inefficiencies—only to realize I’ve missed the point. To design from memory, you have to battle both the detachment from reality and the romanticism that memory creates. No plan is perfect. The dimensions are not exact. Details are missing. That’s intentional. These are not drawings of houses; they are drawings of how those houses lived inside me.

Tactile Memory

Memory often lives in touch.

The floral wallpaper in my dad’s half-bath.

The black carpet in the hallway.

The warmth and rhythmic ticking of the radiator beside my bed.

The distorted glow of snowplow lights passing through my childhood window late at night.

I remember my younger brother’s bedroom—a converted closet and walk-through to the attic. Cave-like. Compact. Simple. That space shaped him as much as anything else did. I remember the views from my older brother’s room, looking out toward the front yard. The laundry chute tucked into our closets. The proximity and privacy of our bedrooms in both the Scott Street house and the Old Green Bay Road house.

I remember the sound of my dad playing the piano late at night, the vibration traveling through the wood floorboards. I learned the house by sound—each room with its own echo, its own volume. You could tell where someone was without seeing them.

Living Abroad, Learning Economy

In Geneva, memory expands outward. A glimpse of the Jura Mountains. A partial view of Lac Léman. Simple but elegant window latches that let hot air escape in summer and catch a gentle breeze off the lake. Operating them felt like a small ritual—one that feels undervalued in much of Western residential design.

The parquet floors in each apartment. Doing laundry in the kitchen. Internal courtyards that stayed cool in summer while pulling in ambient light. Modest apartments, yet celebrated entry stairs—terrazzo floors, carved wood railings, an atrium treated as a shared interior room rather than a leftover space.

Despite their size, these apartments felt luxurious because of care and material quality. In the United States, apartments often prioritize efficiency and amenities—rooftop decks, lounges, balconies that rarely get used or remembered. Europe benefits from a longer history of preservation; the U.S. is far quicker to demolish. Capital moves fast. Memory does not.

The compact kitchens taught me what was truly necessary. The separation of toilet and washroom felt novel at first, then obvious. I still don’t understand why this hasn’t caught on more widely in America—especially in affordable housing, where thoughtful material use and spatial logic make the greatest difference.

People don’t remember rooftop grills.

They remember terrazzo underfoot.

They remember a beautiful backsplash.

They remember zellige tile catching light in a shower.

Chicago, College, and Improvised Architecture

I lived in a house in Chicago converted into three units—one per floor. I had the attic. The lock was a push button. The space was “open concept,” but it wasn’t undifferentiated. It was divided by moments.

A folding ladder stair hidden in the wall, leading to a storage loft.

A short stair to a roof hatch opening onto a tiny private patio for two, with a view of the skyline.

A back deck that felt perpetually on the verge of collapse.

Built-in drawers instead of furniture, so I didn’t have to buy anything.

Exposed rafters.

A potbelly stove so hot lighters would explode on it.

The floor sloped like a ship’s deck. If you spilled something on the counter, it would run toward the sink. It creaked. It leaned. It felt alive.

In college, we lived in a house perfect for two—simple, private, generous enough to host friends. The front porch was everything. A place to gather. A place to watch events unfold. Architecture as social infrastructure.

Memory as Design Tool

It makes me wonder why certain spaces stay with us so vividly.

Is it scale?

Light?

A unique element—a ladder, a door, a skylight?

Or is it the period of life itself, when certain moments carry more weight and memory sharpens?

The point of all this, for me, is understanding what we hold onto subconsciously—and how that shapes our decisions about space. If you’re trying to recreate a memory, you have to understand all the influences that disrupt it. The feeling you’re chasing will always be different today than it was back then.

Memory is a tool, but it isn’t a blueprint. What lingers is not the room itself, but how it made us feel.

That—more than square footage or style—is the poetics of space.

Sketches clockwise from top-left; Scott Street, Winnetka, Illinois; Old Green Bay Road, Winnetka, Illinois; E Withrow Street, Oxford, Ohio; Orchard Street, Chicago, Illinois; Blvd Carl-Vogt, Geneva, Switzerland; Rue Muzy, Geneva, Switzerland